Inside-Out

San Angelo: September 20, 2018 - March 24, 2019

Henry Morrison Flagler Museum, Palm Beach, FL: October 15, 2019 - January 5, 2020

Farmington Museum, Farmington, NM:

March 6, 2020 – July 12, 2020 [now extended to Jan. 17, 2021, due to closures from COVID 19]

This is a traveling exhibit about American women. It is about how women have shaped American society, and about the undergarments that have shaped them.

We are deeply grateful for the sponsors, lenders, experts, and encouragers who helped make this exhibit a reality. And though this is an exhibit about American women, we offer a very special "Thank you" to our Canadian collector-lenders, for the spirit of international cooperation and solidarity.

View the Exhibit Catalog:

Here are links to absolutely top-notch articles about our Inside-Out exhibit:

- From Palm Beach Daily News:

https://www.palmbeachdailynews.com/entertainment/20191104/what-do-womenrsquos-undergarments-say-about-their-fight-for-equality-lot-says-show-at-flagler-museum - Palm Beach Coastal Star, December of 2019

The exhibit explores three central themes:

1. The perceived roles of women in American culture as they have changed over time, from the Federalist period to the present, and how those roles have shaped—and been shaped by—what women wear.

2. Feminist ideas and movements since the nation’s earliest days, and the significant role of undergarments relative to those movements.

3. The outward appearance and silhouette of stylish American women over the centuries. The design, intention, and transition of women’s undergarments that helped create the silhouettes.

The exhibit is divided into eight chapters of American history:

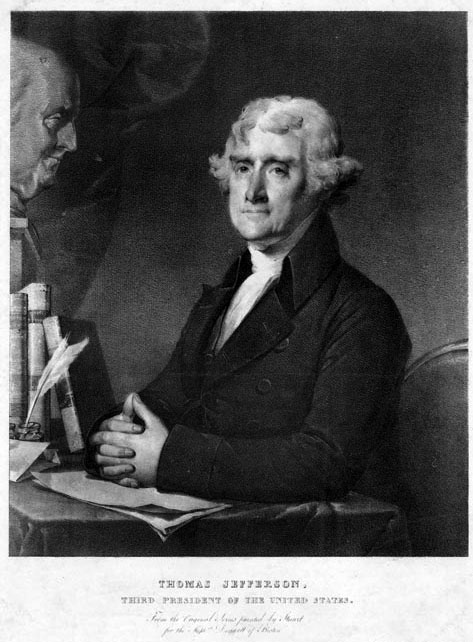

Chapter 1: The Federalist Period

Revolution and Freedom: Clothing and the American Identity

Discarding the identity of an English Colony, early Americans considered the importance of clothing as it reflected the new American identity. Rejecting the requirements of “court dress,” President Thomas Jefferson received the newly appointed British ambassador, Anthony Merry, at the President’s House in 1803. Ambassador Merry was formally attired in an embroidered coat and breeches, President Jefferson wore a dressing gown and slippers. Jefferson helped establish a new, relaxed and less formal way of dressing.

Discarding the identity of an English Colony, early Americans considered the importance of clothing as it reflected the new American identity. Rejecting the requirements of “court dress,” President Thomas Jefferson received the newly appointed British ambassador, Anthony Merry, at the President’s House in 1803. Ambassador Merry was formally attired in an embroidered coat and breeches, President Jefferson wore a dressing gown and slippers. Jefferson helped establish a new, relaxed and less formal way of dressing.

More relaxed, perhaps, but still fashion-conscious, American women adopted the European fashions that followed the French Revolution, taking inspiration from Classical ideals and in lighter materials and colors. First Lady Dolley Madison (1809-1817) was the celebrity fashionista of the period, and helped America keep up with the latest trends. The popular Empire style of the early 1800s was the antithesis of the formal, large and cumbersome dresses of the 18th century. The ease of the new style of dressing was reflected in the undergarments: The restrictive stays and hoops of the previous era were replaced by light chemises and relaxed waistlines. Corsets (if worn at all) were comfortable and did nothing to cinch the waist, but very effectively pushed up the breasts.

As for changing restrictive norms, even prior to American independence, American women struggled for their rights: In 1776, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband, John, in Philadelphia, urging him and the other members of the Continental Congress to “remember the ladies” when fighting for America’s independence, and to give women a voice in the political process. “We are determined to foment a rebellion,” she wrote, “and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation.” They should have listened.

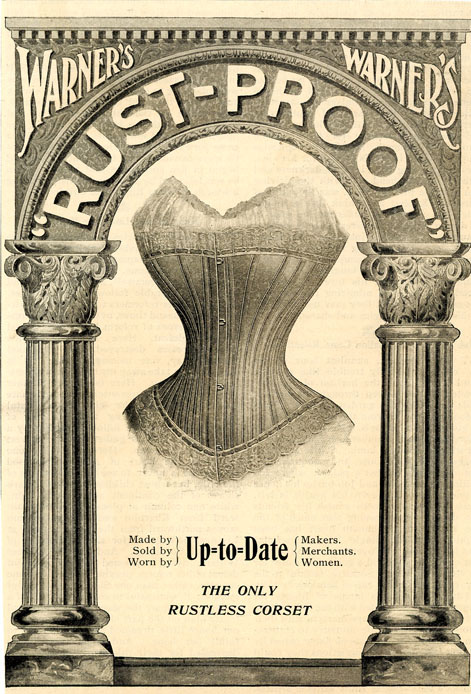

Chapter 2: The Victorian Period 1850-1900

Structurally Engineering the Female Silhouette

“Build it big” was a goal of the Victorians, and their ideal female silhouette was no less a feat of structural engineering than the Eiffel Tower, the Crystal Palace, or the Brooklyn Bridge. First, reinforced corsets were required for the perfect hourglass figure. Then, to properly fill out the dress, elaborate contraptions made of wire, wood, spring coils, horsehair, and any other type of stiff material were layered on over the corset! The huge bell-shaped skirts of the 1850s and 60s required a cage or hoop crinoline underneath. After 1870, crinolines were replaced by bustles, changing a woman’s lower half from bell-shaped to protruding in the back. A popular style of sleeve in the 1890s, known as the leg o’ mutton, sometimes needed sleeve plumpers—bulky shoulder cages with fabric covers. At the end of the 1890s, the ideal silhouette changed again, this time to the shape of an “S.” Women’s bosoms and buttocks were forced up and out, using a long, tight corset that squeezed and pushed the body to achieve the desired shape. Some Victorian women tried to change these restrictive fashions, without much success. The “bloomer costume,” named after women’s rights activist Amelia Bloomer, enjoyed a brief popularity during the 1850s.

“Build it big” was a goal of the Victorians, and their ideal female silhouette was no less a feat of structural engineering than the Eiffel Tower, the Crystal Palace, or the Brooklyn Bridge. First, reinforced corsets were required for the perfect hourglass figure. Then, to properly fill out the dress, elaborate contraptions made of wire, wood, spring coils, horsehair, and any other type of stiff material were layered on over the corset! The huge bell-shaped skirts of the 1850s and 60s required a cage or hoop crinoline underneath. After 1870, crinolines were replaced by bustles, changing a woman’s lower half from bell-shaped to protruding in the back. A popular style of sleeve in the 1890s, known as the leg o’ mutton, sometimes needed sleeve plumpers—bulky shoulder cages with fabric covers. At the end of the 1890s, the ideal silhouette changed again, this time to the shape of an “S.” Women’s bosoms and buttocks were forced up and out, using a long, tight corset that squeezed and pushed the body to achieve the desired shape. Some Victorian women tried to change these restrictive fashions, without much success. The “bloomer costume,” named after women’s rights activist Amelia Bloomer, enjoyed a brief popularity during the 1850s.

Women in the Victorian period were bound, but they were also determined. The abolitionist movement fought to end slavery, and many of its leaders were women. Numerous abolitionists also supported women’s rights and the leadership of the two movements initially overlapped. Frederick Douglass gave an influential speech at the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, which was the first women’s rights convention held in America, and Sojourner Truth spoke at the 1850 convention. These Conventions marked the official beginning of the long battle for women’s right to vote in our nation. Unfortunately, in the tormented years following the Civil War, supporters of civil rights and supporters of women’s rights diverged. Prominent women’s suffragists ignored the 2.2 million black women in America, 2 million of whom had been enslaved prior to the Civil War, and some even contested the 15th Amendment (1870), which gave black men the right to vote. Not until 100 years later did black and white women begin to fight side-by-side for equal rights.

Chapter 3: The Roaring 20s

Upheaval and the Jazz Age

The effects of World War I changed attitudes and everyday aspects of people’s lives. The loss of millions of young lives to war and the Spanish influenza epidemic spurred an attitude of carefree existence. In 1920, nearly 150 years after American independence, women finally won the right to vote—and a sense of freedom. Gone were the stuffy clothes and regimented schedule. The new style was loose, drop-waist dresses, and the desired figure was more boyish. The hourglass corset and multiple layers of underpinnings were replaced with a bra and pair of light, baggy knickers or a combination garment called a cami-knicker. To achieve the popular gamin look and wear the “flapper” dress, voluptuous women donned a long, straight corset or a bust flattener. The era was punctuated with the new popularity of the cocktail party, despite the fact that alcohol was illegal because of Prohibition! Private citizens made their own liquor at home and speakeasies and nightclubs were filled with drinking, dancing and the newest craze in music—jazz. Women dared to cut off their hair, and they smoked and drank freely in mixed company, partying just as hard as the men. This footloose and fancy-free lifestyle, however, abruptly ended with the stock market crash of 1929. The Hollywood glamour of the Great Depression belied the dire straits in which most of the nation found itself, but the look it presented—trim women wearing long, columnar, backless dresses, close-cropped hair, and elegantly smoking cigarettes in holders—evolved from the fashions of the Roaring 20s.

Women in the Workforce

Emerging from the Great Depression, America entered World War II. Women entered the workforce and the war effort in large numbers. Undergarments did not change much from the 1930s, but women working in factories and in auxiliary military roles demanded less constrictive and more supportive undergarments. Underpants were still somewhat loose-fitting, but hugged the body more closely. Panty-girdles were invented to be worn under slacks or coveralls. The Saf-T Bra was introduced to protect women from workplace accidents. During the war, nylon was redirected towards the war effort and silk was no longer imported from Japan. Many women made their own undergarments or repurposed older garments worn during the Depression. Others, excited to be earning a paycheck, did their part to make sure the lingerie industry stayed alive by buying new undergarments, which were marketed to these working women.

One of the many contributions made by American women during the Second World War was their service as WASPS (Women Airforce Service Pilots). Between early 1943 and December 1944, Avenger Field in Sweetwater, Texas was the training ground for 1,074 women who served as pilots during the war. WASPS did not fly in combat, but they transported military planes, carried cargo, towed targets for live anti-aircraft gun practice, and performed other vital functions. 38 WASPS gave their lives in the service of the United States. In 1974, WASPS were officially recognized as military veterans. During WWII, women proved that they could do anything—fly planes, build ships, wire electronics, fix cars, decode enemy transmissions, and even play professional baseball.

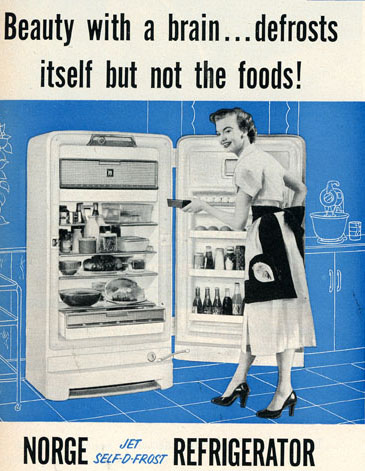

Chapter 5:

The 1950’s

Grace Kelly and Housework in Heels

In a decade’s time the American woman went from riveting to vacuuming. Men returning home after WWII resumed their jobs and women went back to working in the home. Utility-based clothing was no longer needed. In the post-war years, a new, glamorous, hyper

-feminine ideal emerged, inspired by Christian Dior’s “New Look.” The fashion consisted of graceful full skirts, perfectly coiffed hair, pearl necklaces and high heels, worn even during housework. Sleek, futuristic designs were incorporated into everything, including appliances, furniture, cars and brassieres. The ideal female silhouette was trim through the waist with a perky bust. Underwear designs that emerged in the 1940s continued into the 1950s with a few modifications: The cups of the bras became pointier, strapless bras became necessary for the dresses and blouses of the day, and new man-made materials were incorporated, along with bright colors and sexy lace overlay. This new ideal of feminine beauty was presented in a range of looks, from the provocative sweater girl, to the elegant film actress Grace Kelly and dutiful fictional TV mom June Cleaver (played by Barbara Billingsley).

-feminine ideal emerged, inspired by Christian Dior’s “New Look.” The fashion consisted of graceful full skirts, perfectly coiffed hair, pearl necklaces and high heels, worn even during housework. Sleek, futuristic designs were incorporated into everything, including appliances, furniture, cars and brassieres. The ideal female silhouette was trim through the waist with a perky bust. Underwear designs that emerged in the 1940s continued into the 1950s with a few modifications: The cups of the bras became pointier, strapless bras became necessary for the dresses and blouses of the day, and new man-made materials were incorporated, along with bright colors and sexy lace overlay. This new ideal of feminine beauty was presented in a range of looks, from the provocative sweater girl, to the elegant film actress Grace Kelly and dutiful fictional TV mom June Cleaver (played by Barbara Billingsley). Post-war America sought to project the image of success and domestic tranquility, even as the Cold War raged. And other, stronger undercurrents (that boiled over in the next decade) rippled the seemingly-flawless surface. Racial injustice was flourishing and the catalysts that effectively began the Civil Rights Movement happened in the 1950s, including Brown vs. Board of Education and a brave and dedicated woman, Rosa Parks, who refused to give up her seat on a segregated bus in 1955.

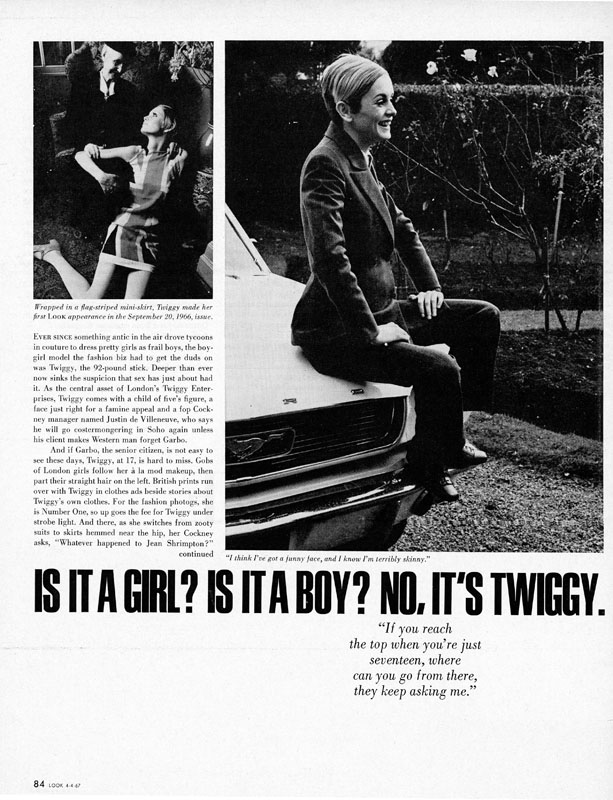

Chapter 6: The 1960s and 1970s

Counterculture and Feminism

In 1960, the FDA approved “the Pill” for use as a contraceptive. In the decade that followed, American women began to graduate from college and start careers at a higher rate than ever before. Women aggressively challenged previous ideals of feminine duty, beauty, and sexual norms. The widespread use of corsets and girdles came to an end and suddenly there were more choices: Heels or flats. Mini skirt or long, billowy dress. Slips and bras were optional. Pantyhose were developed for wear with short skirts and without girdles.

In 1960, the FDA approved “the Pill” for use as a contraceptive. In the decade that followed, American women began to graduate from college and start careers at a higher rate than ever before. Women aggressively challenged previous ideals of feminine duty, beauty, and sexual norms. The widespread use of corsets and girdles came to an end and suddenly there were more choices: Heels or flats. Mini skirt or long, billowy dress. Slips and bras were optional. Pantyhose were developed for wear with short skirts and without girdles.

The social and political upheaval of the 1960s was astonishing and explosive. It was a tumultuous and deeply divisive era that included the assassinations of JFK, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy; the Vietnam War; the Civil Rights Movement; Black Power; student protests; and the beginning of the long struggle for women’s rights in the workplace and in society. The protest of the 1968 Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City was a major milestone in the women’s liberation movement, when the protestors gathered on the boardwalk and decried the pageant as being both racist and misogynistic. The organizers set out the Freedom Trash Can, into which women were encouraged to toss bras, girdles, fashion magazines, curlers, high heels, and “other instruments of torture.” Simultaneously, the Miss Black America Pageant, a protest organized by another group, was held in the nearby Ritz Carlton, also denouncing unrealistic and uniformly white beauty standards. The changes and challenges of the times were reflected in the designs of clothing and undergarments. Women who had never attended a protest march still wore the colorful, psychedelic patterns, short skirts, and lightweight undergarments that defined the fashions of the era.

Chapter 7: The 1980s and 90s

The Mtv Era: Underwear or Outerwear?

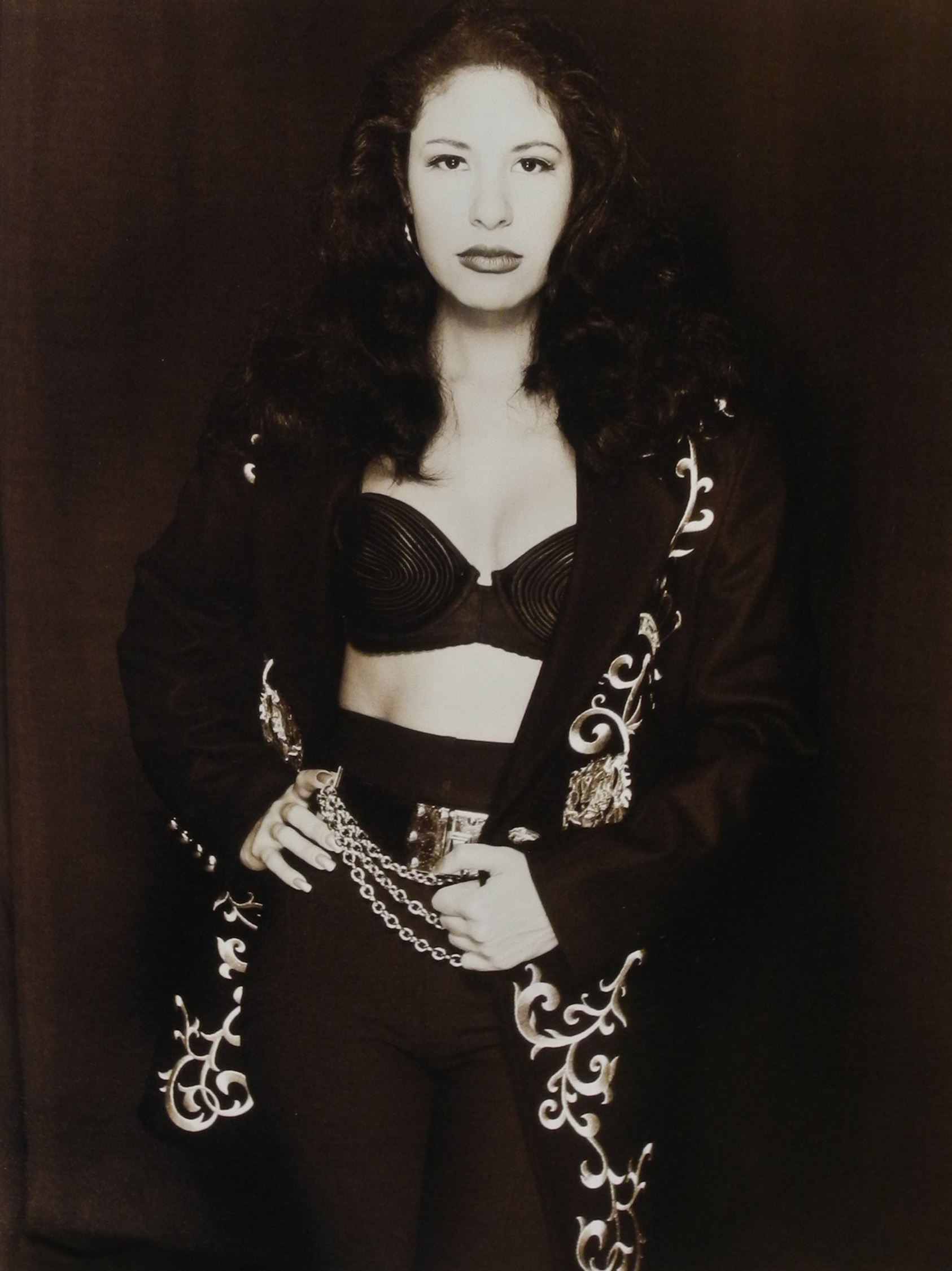

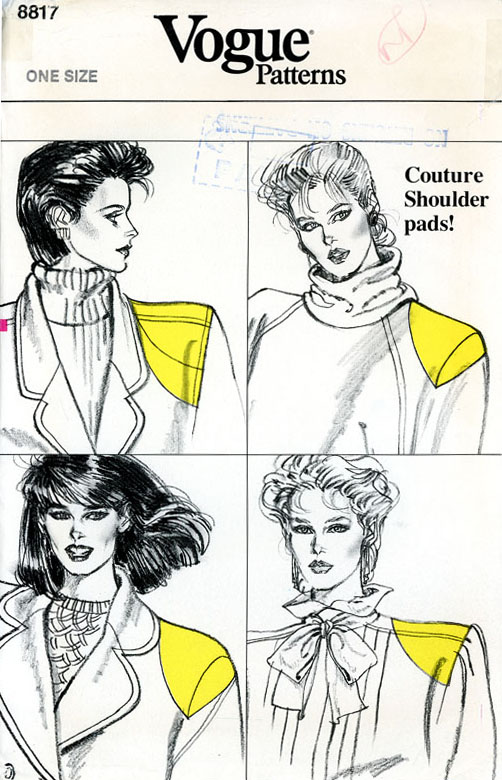

The Memphis Design Movement represented an irreverent departure from prevailing design models of the post-WWII, mid-century era, and influenced everything from furniture to fashion. Pop icons like Madonna and Selena ushered in a period where underwear played a starring role, not just a supporting role. The idea of underwear as outerwear became mainstream fashion. Women fought to break the glass ceiling wearing lacy bustiers under power suits, and also began fighting back against sexual harassment in the workplace. In their leisure time, women showed off their aerobicized bodies in high-cut lingerie, swimsuits, and leotards. Bras and shoulders were padded once more. Underwear was worn proudly, almost aggressively.

The Memphis Design Movement represented an irreverent departure from prevailing design models of the post-WWII, mid-century era, and influenced everything from furniture to fashion. Pop icons like Madonna and Selena ushered in a period where underwear played a starring role, not just a supporting role. The idea of underwear as outerwear became mainstream fashion. Women fought to break the glass ceiling wearing lacy bustiers under power suits, and also began fighting back against sexual harassment in the workplace. In their leisure time, women showed off their aerobicized bodies in high-cut lingerie, swimsuits, and leotards. Bras and shoulders were padded once more. Underwear was worn proudly, almost aggressively.

By 1980, women had long since proven that they had the ability to work alongside men, but they still faced the more insidious challenges of discrimination, disparity in pay, and sexual harassment. The term “glass ceiling” began to be commonly used to describe the invisible barrier that stopped women from reaching the top executive positions and highest paying jobs. For the first time in American history, sexual harassment legislation was introduced. The bright, color-block designs, bold geometric shapes, and wide, padded shoulders, worn together with short skirts and bra tops, of popular 80s and 90s fashions exuded confidence and ambition coupled with unashamed femininity.

“Selena” Copyright 1993, Al Rendon

Chapter 8: The Contemporary Age

What Goes Around, Comes Around

Design combinations of the last two hundred years have been incorporated into the popular fashions of today. For undergarments, women are faced with an overwhelming array of choices, ranging from no underwear at all, to androgynous cotton briefs, to constrictive shape-wear and waist-training corsets. The female silhouette we see in popular media and advertising is surgically, mechanically, and digitally manipulated. Nevertheless, women have never been so free to choose what they wear, and contemporary feminist movements remind us that what a woman chooses to wear does not define her, nor does it give anyone permission to judge her.

Design combinations of the last two hundred years have been incorporated into the popular fashions of today. For undergarments, women are faced with an overwhelming array of choices, ranging from no underwear at all, to androgynous cotton briefs, to constrictive shape-wear and waist-training corsets. The female silhouette we see in popular media and advertising is surgically, mechanically, and digitally manipulated. Nevertheless, women have never been so free to choose what they wear, and contemporary feminist movements remind us that what a woman chooses to wear does not define her, nor does it give anyone permission to judge her.

In this era, technology has provided a powerful tool for social activism. Social media has proven it can topple governments, and it has been the platform for current discussions about body autonomy, family and paternity leave, body positivity, and gender identity. Social media is credited with the unprecedented turnout at the Women’s March on January 21, 2017. Half a million people participated just in Washington, D.C., and an estimated 4 million around the nation. #MeToo generated more than 12 million posts within a day’s time. It shed light on the pervasiveness and persistence of sexual harassment, assault, victim-blaming, and looking the other way in our society. Social media activism is also helping us embrace the idea that any person of any body type should be able to wear anything they choose. Even with all the progress, we still have a long way to go before we, as a culture, stop shaming women for their body type, race, gender, or clothing choices.

To learn more about this traveling exhibit, click here!

EXHIBIT EVENTS

Exhibit Opening

Thursday, September 20, 2018

5:00 PM - 9:00 PM

Join us for a night of free refreshemtns, food, music and art

at the San Angelo Museum of Fine Arts

1 Love Street, San Angelo, TX

Special Lecture & Tour

Friday, September 21, 2018

5:30 PM

By Collector John Rogers of

Victoria, British Columbia

at the San Angelo Museum of Fine Arts

1 Love Street, San Angelo, TX

‘Let’s Misbehave’ Party

& Fundraiser

Friday, September 28, 2018

6:30 PM

An outrageous and delightful

evening of fine dining, dancing,

and celebration in recognition

of the Inside-Out exhibit.

$500 Per person

Ticket purchase required,

Click HERE to visit the purchase tickets page

or call 325-653-3333 for more information.