This project is made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, and is also supported by the Texas Commission on the Arts, Texas Folklife, and the San Angelo Cultural Affairs Council. All research, fieldwork, text and photography was done by Folklorist Douglas Manger of Seguin, Texas.

Introduction

The word “tradition” comes from the Latin traditionem, “a handing down, a giving up.” Though the meaning suggests a static, unchanging state, as for folklife and folk art -- that is, living traditions learned informally within a shared community passed from one generation to the next -- the opposite is true; they are both equally expressive of change, subject of course to the whims of the times.

By the 1870s, permanent Anglo and Hispanic settlements were being established in the Concho Valley. Land was the drawing card for many early settlers, grazing land to raise cattle, sheep and goats. By 1900, the population in the region numbered 20,000, concentrated largely around San Angelo. With the new growth the need for skilled craftsmen became ever more critical -- farriers to shoe horses, blacksmiths to mend farm and ranch equipment, sheep shearers, butchers, bakers, tailors, seamstresses, and, of course, gearmakers to make tack, boots, chaps and chinks for the working cowboy.

As these settlements took hold, folkway traditions came to light -- storytelling, foodways, music and dance traditions -- cherished ways borne in from another place or the Old Country itself. As for occupational folkways, embedded within were trade skills passed from master to apprentice, or in the case of domestic arts, home-craft skills shared and taught in family circles.

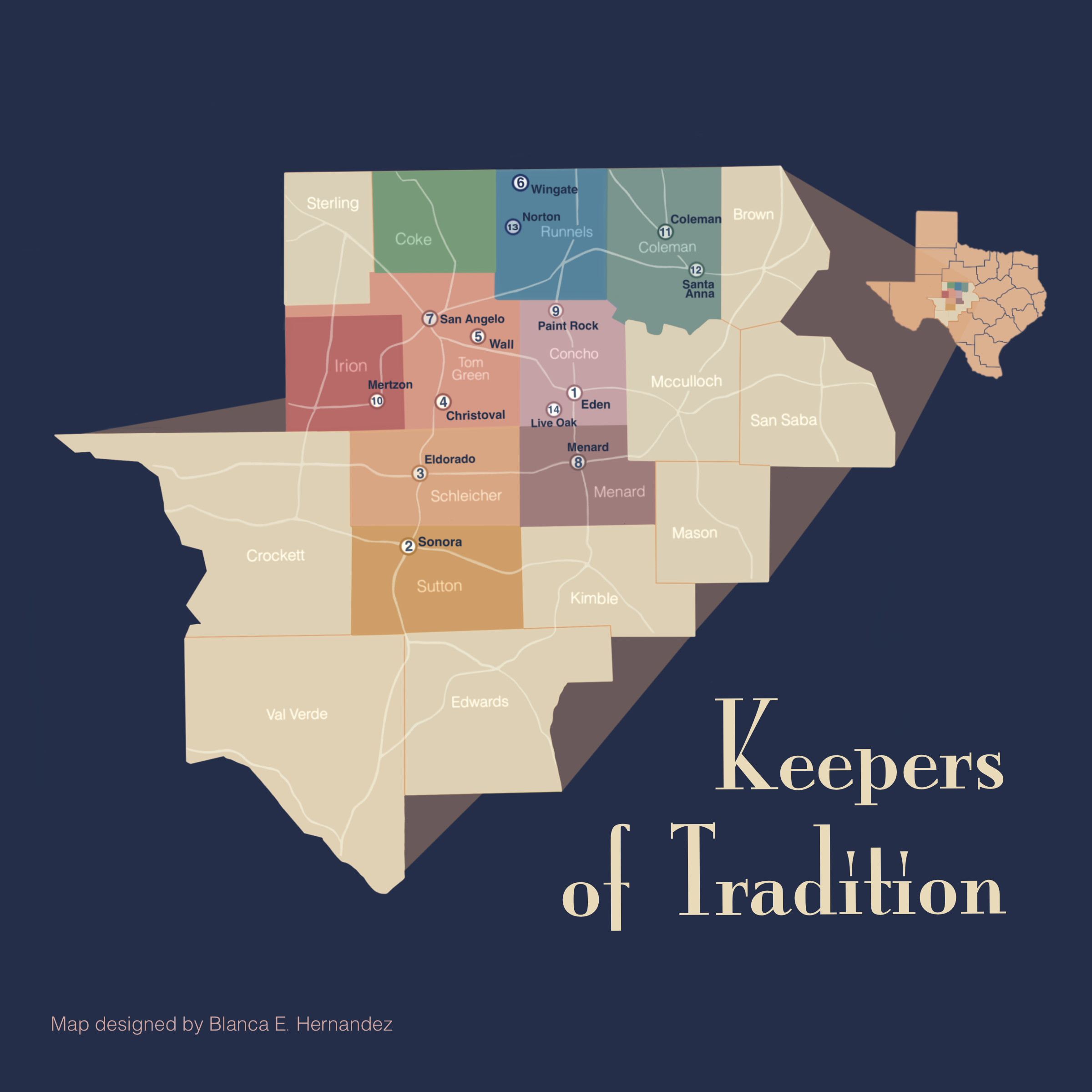

In this exhibit, an outgrowth of fieldwork conducted during the first phase of the True Texas initiative, 22 craftsmen are featured from 9 of the 18 counties that make up the Concho Valley Region. Be they forged or fired, etched or stitched, crocheted or woven, many of the handworked craft forms featured here have been an integral part of the folkways of the region since those first early settlers arrived.

As you acquaint yourself with these tradition keepers consider their shared aesthetic. For one, to be sure, their work does not cater to rapidly changing fashions. The forms these makers manipulate remain predictable. The repetition of style in the work is an affirmation of tradition, yet some deviation is the norm as makers mature in their trade. Each work is a time capsule of sorts, an embodiment of how-to knowledge, dutifully passed, one generation to the next, one maker to the next. Outside the box artisan works are also shown here in recognition of makers-being-makers, eager to push the boundaries of their craft as their imagination takes them.

The San Angelo Museum of Fine Arts’ True Texas initiative honors the region’s working folk and traditional artists of today. Be they bootmaker, quilter, or artisan blacksmith, it is their distinctive work that contributes immeasurably to the character of the Concho Valley Region. Accordingly, the Museum is committed in the long term to promoting the traditional arts in the region through a range of activities to include exhibits, workshops, and the creation of skills preservation training programs with regional partners.

Click on the artists' names to jump to their sections:

Eden | Concho County

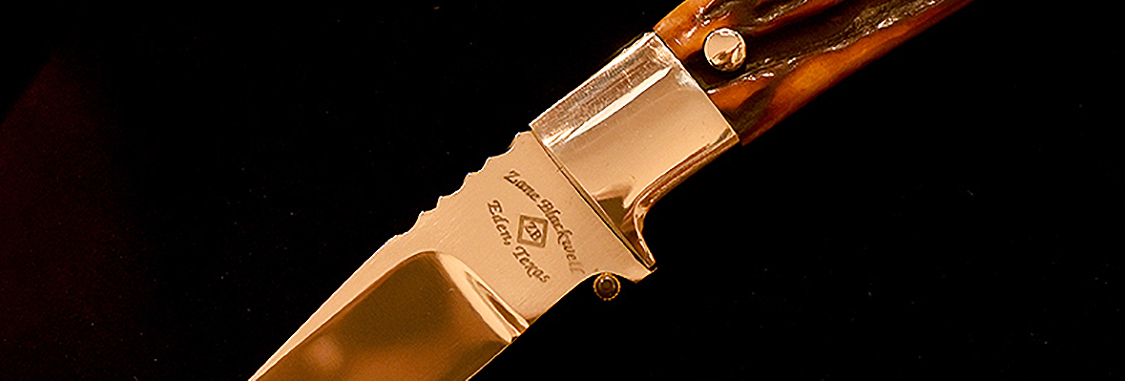

Knifemaker, Blackwell Custom Knives

I pride myself that the knife feels like an extension of your hand or arm -- scalpel sharp. You want the knife to do the work and make it as easy on you as possible.

In the winter months, when whitetail deer hunting season opened in Texas, Zane Blackwell learned early on how critical it was to carry a good quality harvesting knife. “Growing up on a ranch in Central Texas [Zane’s father was the ranch foreman] everyone I knew carried knives on a daily basis. I was never without a knife and wanted to make them for as long as I can remember.” For Zane, the issue became, where to begin.

In 1995, Zane took a leap of faith with the launch of his custom knifemaking business. Weldon  Whitley of Odessa, Texas, and Loyd McConnell of Marble Falls, Texas, stepped up to give him the necessary tutelage to begin his work. For Zane, building knives is all about the details: tapering the tang so it’s evenly balanced at the guard; milling a slot for the guard to ensure a good tight fit; rope filing the spine of the blade to give the knife almost a jewelry effect; and for those clients out for the best possible fit, modeling their hand with clay beforehand. Comfort, ease of use, a blade that is scalpel sharp, all are critical selling points for Zane. “I pride myself that the knife feels like an extension of your hand or arm.”

Whitley of Odessa, Texas, and Loyd McConnell of Marble Falls, Texas, stepped up to give him the necessary tutelage to begin his work. For Zane, building knives is all about the details: tapering the tang so it’s evenly balanced at the guard; milling a slot for the guard to ensure a good tight fit; rope filing the spine of the blade to give the knife almost a jewelry effect; and for those clients out for the best possible fit, modeling their hand with clay beforehand. Comfort, ease of use, a blade that is scalpel sharp, all are critical selling points for Zane. “I pride myself that the knife feels like an extension of your hand or arm.”

With a boost from his appearance on the cable show, “Forged in Fire, Knife or Death,” Zane has built an international clientele. As for his next challenge, Zane is keen on fashioning his own blades the old-time traditional way, using a forge, hammer, and anvil.

Sonora | Sutton County

Silversmith, Lee Silver Co.

My customers know a Lee Bloodworth buckle is going to be 100% of my best effort using precious metals; silver, gold, or a combination of both, and genuine stones.

Lee Bloodworth’s love of silverwork, instilled in him by his grandmother, might never have  developed were it not for a curious twist of fate. In 1952, a severe drought in Sutton County forced his father to move the family to New Mexico. During their six year stay, Lee’s grandmother, Ida Halbert Bloodworth, who was one-quarter Choctaw, traded for silver jewelry crafted by the local Isleta Pueblo Indians. In 1958, when the drought finally broke in West Texas, the Bloodworths returned to the family ranch outside of Sonora. “Along with that, we brought the affection that we had for the Indian jewelry, the silversmithing … that’s where it all began … I was mesmerized by the silversmithing … from New Mexico.”

developed were it not for a curious twist of fate. In 1952, a severe drought in Sutton County forced his father to move the family to New Mexico. During their six year stay, Lee’s grandmother, Ida Halbert Bloodworth, who was one-quarter Choctaw, traded for silver jewelry crafted by the local Isleta Pueblo Indians. In 1958, when the drought finally broke in West Texas, the Bloodworths returned to the family ranch outside of Sonora. “Along with that, we brought the affection that we had for the Indian jewelry, the silversmithing … that’s where it all began … I was mesmerized by the silversmithing … from New Mexico.”

When Lee was five his mother commissioned a Mr. Hougin, a Pueblo Indian silversmith, to make small belt buckles with cattle brands on them for Lee and his two brothers. Years later, when his buckle went missing, Lee put his mind to replacing it. With the cost of a commissioned piece out of reach, Lee settled on a plan. He would craft a new buckle himself by re-purposing the brass lining from an old windmill cylinder. Although the end result was crude, it was a starting point. “From then on I just built on that.”

Mostly self-taught, over the course of his 35 year career, Lee has kept up his skill sets by studying the work of other accomplished silversmiths past and present. One of Lee’s specialties is creating one-of-a-kind belt buckles to highlight the cattle brands of local ranchers. Given Lee’s reputation, once a rancher commits to investing in a Bloodworth buckle, solid silver or gold through and through, they know in time the buckle will become a treasured heirloom piece to be passed down from one generation to the next.

(Back to top)

Eldorado | Schleicher County

Healer

I don’t know why they believe in me … I still say it’s not me, it’s [their] faith.

Working from her home in the barrio on the north side of Eldorado, Dora de los Santos Bosmans offers help to community members suffering from susto (scare or fright), ojo (the evil eye), empacho (indigestion) -- or in the case of an infant -- caida de mollera (a fallen fontanelle or soft spot on the top of the child’s head).

Born in Del Rio in South Texas, Dora’s parents moved north to Eldorado to pick cotton. As migrant workers in the 1960s the family traveled as far as California to find work. With a troubled father who was often away, at a young age Dora was left to look after her mother and her two sisters. Her formal education ended abruptly in the third grade with an all too familiar narrative: picking bitterweed for $2.50 a day to help feed the family.

Ever curious growing up, Dora was drawn to the folk remedies practiced by the women elders in the barrio, remedies she would later be called upon to use. When that time finally came, Dora never hesitated. As the word spread about her gift for healing, community members began to seek her out. “The people who come are somebody we know,” Dora’s daughter, Thelma, relates. “When they come they are afraid. Most of them don’t know the tradition.”

Perhaps Dora’s work as a healer was inevitable. After the loss of two of her children to cancer, the local priest offered Dora heartfelt words of consolation: “You are really loved by the Lord because you know His pain.”

(Back to top)

Christoval | Tom Green County

Bit & Spur Maker, Capron Bits & Spurs

Creating stories in the work is fine … yet when the customer creates his own stories with the piece, it then becomes so much more connected to that person’s heart and soul.

The salt flats, a dry basin at the foot of the Guadalupe Mountains in far West Texas, is unforgiving territory where the wind blows no end across a treeless landscape. It’s a place where the stock tank doubles as a bathtub for local ranch folk. It’s also the place where Wilson Capron felt right at home. At the time his father, Mike Capron, a diehard cowboy and emerging Western artist, managed a ranch on the flats. “My dad always said, sorry country breeds great people. There were a lot of thirsty afternoons, hungry afternoons, but it builds character. It’s fun. I loved it.”

After graduating high school, Wilson headed for Tarleton State University. Once his freshman year was behind him,  Wilson moved in with the Greg Darnall family. Greg was a good friend of Wilson’s father. Not one to overlook a good hand, Greg eventually offered Wilson a job in his growing bit and spur making business. Working in a production setting, making 1,500 bits and spurs a month, bored Wilson to tears. That would all change a year and a half later, however, when Greg gave him the opportunity to learn engraving. Wilson ended up staying on for another year and a half before making his way back home. “About six months to a year after leaving Greg I found myself working full time in the shop trying to keep up. I woke up and found myself as a full time bit and spur maker, but I didn’t set out to be one.”

Wilson moved in with the Greg Darnall family. Greg was a good friend of Wilson’s father. Not one to overlook a good hand, Greg eventually offered Wilson a job in his growing bit and spur making business. Working in a production setting, making 1,500 bits and spurs a month, bored Wilson to tears. That would all change a year and a half later, however, when Greg gave him the opportunity to learn engraving. Wilson ended up staying on for another year and a half before making his way back home. “About six months to a year after leaving Greg I found myself working full time in the shop trying to keep up. I woke up and found myself as a full time bit and spur maker, but I didn’t set out to be one.”

Today, with his sterling reputation, Wilson’s challenge is to translate what the customer is trying to say into a steel bit, or a pair of spurs. Understanding how they wish to communicate with their horse is key to creating the functionality expected with Wilson’s premium quality work.

(Back to top)

Wall | Concho County

Saddlemaker, Coats Saddlery

Saddle building is like an art. You got to see it. You got to feel it. You got to ride it to appreciate it.

With 11 family members living on the farm in Nebraska, Larry Coats learned from the get-go what hard work was all about. With a liking for handwork, at the age of 19, Larry enrolled in a saddlemaking school in Amarillo, Texas. Once the coursework was behind him he hired on with saddlemaker R. D. Mark in Minatare, Nebraska. Eight months later Larry came full circle, returning home to begin an 11 year run competing on the rodeo circuit in Nebraska and beyond. In his spare time he launched his first saddlemaking business.

In 1987, married for four years with four children, Larry moved his family to Texas for a $5 an hour job at Texas Saddlery in Clarendon: “That’s how bad I wanted to move to Texas,” he recalls. A year later, now with five children, Larry got the itch once again to be on his own. Partnering up with a friend, they rented an old gas station and started building saddles under the name Faith Saddlery.

In 1989, Piland Saddlery in San Angelo came calling. During his two-year stay at Piland’s, Larry built 400 saddles.

When the opportunity to buy into the business didn’t work out as planned, Larry put in his 30-day notice then set about to open his own saddlery business in Wall, Texas.

Today Coats Saddlery, with 15 employees, builds on average 450 saddles a year. Most are team roping saddles priced from $4,500 to $10,000. This past May marked Larry’s 30th year in the saddlemaking trade. Backed up four months or so on orders, it has been that way for the past 25 years.

(Back to top)

Wingate | Runnels County

Dossie Cribbs Western Art

The really popular pieces are the ones that come to me in my dreams.

It’s a tough go to be a bull rider, but that didn’t stop Dossie Cribbs. Coached by his dad, after graduating high school in Rankin, Texas, Dossie set his sights on turning pro. Soon he was off with friends to compete in bull riding competitions Stateside and in Mexico.

But life sometimes has other plans. A highway accident put Dossie into rehab for a year. With his career hopes dashed the question became, what to do now at age 23? “Why don’t you start making some spurs?” was his dad’s suggestion. In his usual fashion, Dossie got with it.

Working out of a tin shed in his back yard, he began to turn out two to three pairs of spurs a week. “They weren’t clean

and pretty like they are today … [but] they were sure affordable enough.”

A year into it, when a friend asked for silver on his spurs, Dossie made arrangements to spend time with silversmith

Seven years on, selling bits and spurs wherever he could at “any jackpot roping,” Dossie landed a spot at the Western Heritage Classic show in Abilene. With the crowd packed in shoulder to shoulder, every item on his table was sold. After that show, Dossie’s business took off.Wilson Capron. The experience opened Dossie’s eyes to a whole new level of craftsmanship.

Today, Dossie’s focus is on crafting custom Western jewelry. “I build pieces from my vision and hope the customers appreciate them.” With a steady demand for his unique creations, trusting his own instincts has been a driving force behind Dossie’s growth as a Western artist.

(Back to top)

San Angelo | Tom Green County

Chicana Folk Artist, Michelle Cuevas Art Works

It doesn’t matter what anybody says about your work. If you love it, that’s all that matters. I just tattooed that on my brain.

Michelle Cuevas was born in Silver City, New Mexico. Michelle has always identified as part Native American and part Hispanic -- Comanche, Sioux, and Yaqui Indian on her mother’s side; Spanish and Portuguese on her father’s side.

In the 1970s and ‘80s, Michelle’s grandfather lived in a modest trailer in Arenas Valley northeast of Silver City. Much of his time was spent in his workshop out back. Up until the age of six, Michelle spent long hours with her grandfather dreaming up her own creations while he crafted his custom lamps. “We were always making something. I was always putting something together with him.” Today, in keeping with the tradition, Michelle creates her new works at her home studio workshop in San Angelo; “I greet him [his ashes] every morning.”

Michelle’s current art works incorporate Aztec designs with other period influences,

including mandala, talavera, and the more contemporary zentangle patterns, “[I have] kind of blended [them] all together and … created my own thing.” From festive, hand-painted plates, stemless wine glasses, and mad-hatter-like triangular cups, to tall box-shaped vessels alive with color; Michelle is finding her own voice in the traditional art world.

Now, another new chapter has been opened. After a chance meeting with a galley owner in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Michelle has begun creating elaborate nichos. “We call them shrines,” Michelle explains, “basically a clock turned around with characters inside (note: In Mexico a nicho box is used as a portable shrine to honor an important figure or loved one).” With the growing demand, Michelle’s work once again has come full circle, inspired by the rich folk culture traditions of Mexico.

(Back to top)

Artist Talks with Michelle Cuevas

Michelle Cuevas talks to us today about the Inspirations behind her Nichos (shrines) and how her work on them began. Check out her artwork in SAMFA's current exhibit - True Texas: Folk & Traditional Arts of the Concho Valley

Menard | Menard County

Folk Artist

I just find the humor in everything.

Belinda Fleming was born to create. With a mother named Queen Dowd, how could she not? On the home front Belinda’s creativity was encouraged at every turn with surprises often in the making. While her mother was occupied outside hanging up the laundry, what better time to cut up a curtain to make a doll dress?

With her creative efforts receiving constant praise from her mother, Belinda never lacked for confidence. Once past her schooling days and married, her love of portrait drawing led to commissions. “I started doing pastel portraits on velour. When I look at them now they are horrible. Then I started doing charcoal on paper at all the surrounding craft fairs.”

Back home in Menard, Texas, though, it would be Belinda’s riotous paintings of  local town folk that would endear her to the community. Using acrylics, her first cartoon-style painting depicted her three sons playing poker with friends. “I did ‘em the way I thought they might look like -- as dogs!” In “Menard Dogs Playing Poker,” Belinda’s knack for selecting just the right breed of dog to depict the personality to be featured, shines forth. The appreciative response to her work set off a series of tribute pieces that continue to this day.

local town folk that would endear her to the community. Using acrylics, her first cartoon-style painting depicted her three sons playing poker with friends. “I did ‘em the way I thought they might look like -- as dogs!” In “Menard Dogs Playing Poker,” Belinda’s knack for selecting just the right breed of dog to depict the personality to be featured, shines forth. The appreciative response to her work set off a series of tribute pieces that continue to this day.

Undaunted in these challenging times, Belinda’s creative zeal lives on in her latest tribute painting, “Menard Law Dogs,” which depicts local law enforcement personnel. So what is the secret to her bright outlook on life? The question is answered in simple terms; “I just find the humor in everything.”

(Back to top)

Patches & Memories Quilting Circle

Patches & Memories Quilting Circle

Eldorado | Schleicher County

Sylvia Griffin, Quilter

I love the quilt. It has so many fond memories. I can see the old fabric in it that probably was some of my daddy’s shirts or my grandmother’s clothes.

To those in the know, all the activity over at the Schleicher County Historical Society & Museum in Eldorado marks the weekly gathering of the Patches and Memories Quilting Circle. The circle has met faithfully on Tuesday afternoons for the past 20 years.

Sylvia Griffin now leads the quilting circle. Their current project, a king-size quilt, will take the group about a year to complete. Now that the piecework has been machine stitched, the quilting itself, done by hand, is well underway. In earlier years two quilting frames were set up at a time; one for the public, and one for members. With a decline in membership, however, just one frame is kept in place.

Sylvia’s interest in quilting took root some 20 years ago after an article appeared in the Eldorado paper announcing the formation of a quilting circle. From the very outset quilting was addictive to Sylvia. “When I got back in it I just wanted to make another one … for my kids, grandkids, and great-grandkids.” Like most members in the group, Sylvia’s roots run deep in the community. Her great-grandparents came to the area in the 1800s to farm and ranch, an occupational tradition that lives on in the Griffin family to this day.

Being open to one another, sharing and praying together, are values embraced by the group. “We love it, we really do,” Sylvia relates, “but you’d have to, to set here and do this. You’d have to have a love for it.”

(Back to top)

Paint Rock | Concho County

Artisan Blacksmith, 3 Nail Ironware

There is something primal about it, something deep inside … when you start forging it’s like learning a new language. You start off simple and you get more complicated as you go.

When artisan blacksmith Randy Kiser looks at a piece of metal work he tries to figure out what it is about the work that attracts him. Through Randy’s eyes, it’s often the imperfections and the abstract parts of the piece that make it beautiful -- the features one doesn’t expect to see.

In 1995, after much prayer and thought, Randy relocated his blacksmith shop to Paint Rock, Texas, the place his  grandparents called home back in the 1920s. One fateful day, settled in with steady business, while doing a search on the Internet, Randy came upon two skillet makers. Fascinated by the scale of their businesses and their ability to stay busy with only one product offering, Randy decided to give it a go and make his own skillet out of carbon steel. When he realized how quickly the skillet heated up and how evenly it cooked, he was sold. Within a short time Randy and his wife, Margie, were selling their own line of forged skillets to customers across the nation.

grandparents called home back in the 1920s. One fateful day, settled in with steady business, while doing a search on the Internet, Randy came upon two skillet makers. Fascinated by the scale of their businesses and their ability to stay busy with only one product offering, Randy decided to give it a go and make his own skillet out of carbon steel. When he realized how quickly the skillet heated up and how evenly it cooked, he was sold. Within a short time Randy and his wife, Margie, were selling their own line of forged skillets to customers across the nation.

The lessons learned after fabricating some 1,400 pans in the past three years have been many. Creating the necessary tooling to make the product even better is always foremost in Randy’s mind. The thought, the care, the time that is put into crafting the skillets has brought rave reviews from customers. “Streamlined and teachable” is also a part of Randy’s mindset, so when it comes time to pass the torch to another maker, he can do so with peace of mind.

(Back to top)

San Angelo | Tom Green County

Designer & Weaver

It’s like I could just do this and never sleep. It is so exiting to me.

San Angelo-based traditional artist, Audrey Legatowicz, has been weaving for over 40 years. Of Russian/Polish ancestry, Audrey’s grandmothers were seamstresses who worked in the textile trade. In her formative years they taught Audrey sewing and crochet.

Audrey’s first exposure to weaving would come much later in life in a Chicago adult education class. In 1980, Audrey

relocated to Texas. Once settled in, she began weaving at the Spindletop retail shop in Dallas. It was the Dallas Handweavers and Spinners Guild Show at a local mall, however, that really opened her eyes. “People want[ed] to buy my creations!”

During her 30 year stay in Dallas, Audrey’s world was all about weaving. After leaving Spindletop, it was on to a private

gallery, and then to a series of consignment shops -- the first her own, the second in partnership with two other weavers. Teaching opportunities followed, initially for the Craft Guild of Dallas, then later for the Plano school system and the Dallas school district’s Booker T.

Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts.

Now, after 10 years of running back and forth to San Angelo twice a year, Audrey has adopted San Angelo as her new home, working out of a studio space at the Old Chicken Farm Art Center.

Ever a student of the craft, it still excites Audrey to explore new weaving structures. “It’s like I could just do this and never sleep. It’s so exciting to me ... I am always open to seeing what I can learn.”

(Back to top)

Mertzon | Irion County

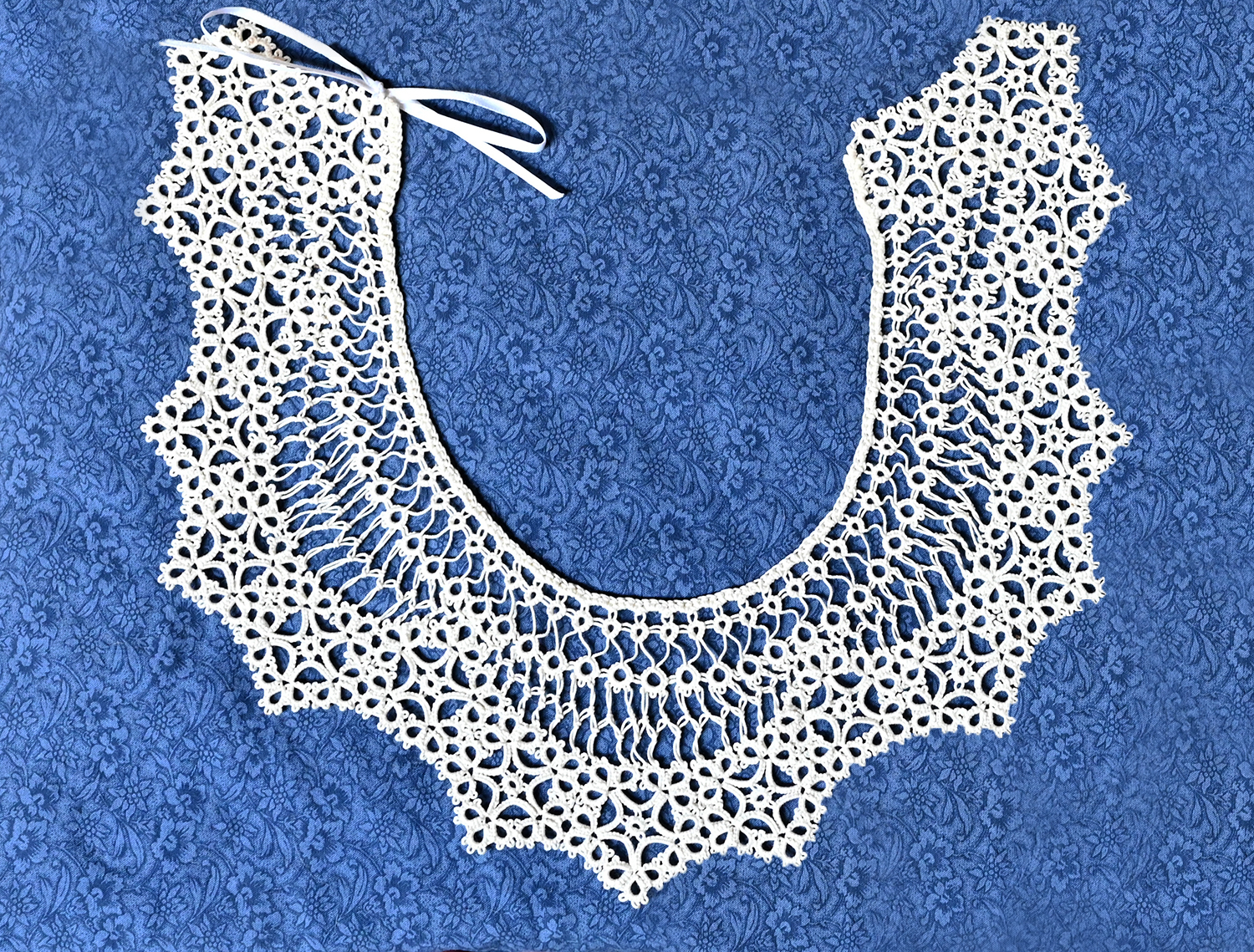

Lacemaker & Seamstress

I had to see if I could do the same things that they did. It strengthens, I think,

the roots that I have to them and to here … I know my grandmother and

mother were proud of my abilities and that is precious to me.

The Lindleys and the Clarks, Valorie Lewis’ great-grandparents from both sides of her family, began ranching in Irion County in the late 1800s, a family tradition that continues to this day “We are very proud -- we’ve been able to keep the ranch together. That’s a hard thing to do in these days.”

For generations, sewing, crochet, quilting, and tatting have been cherished pursuits in Valorie’s family. An eager learner,

by the age of seven Valorie was already making doll clothes using her grandmother’s sewing machine. Later, as she learned new techniques in 4-H Sewing, her work was critiqued by experienced seamstresses. By the time she entered junior high, Valorie was making her own clothes. Some years later a new opportunity would arise: making clothes for her husband and children!

Always eager to share her work, one year at the county fair, to her surprise, Valorie’s entry was rejected. The judges were convinced her machine sewn shirt with hand-stitched embroidery was store-bought, not homemade.

Looking back, apart from her marriage and having children, Valorie considers learning to tat one of her most significant accomplishments. Tying knots to create simple elegant lace is blessed work in Valorie’s eyes.

As for the generational sewing tradition in her family: “I had to see if I could do the same things that they did. It strengthens, I think, the roots that I have to them and to here.” A Cathedral Window quilt is one of Valorie’s current projects, certainly a match for her ambitions with 1,300 pieces required to complete the design.

(Back to top)

Coleman | Coleman County

Assemblage Artists, Haven Meadows Studio

It’s art for people who don’t even realize they like art. That’s one of the things that I really enjoy about the power behind what we do … we have the power to create new collectors where there weren’t any before. -Joshua Meadows

Joshua Meadows has always liked the movie “Predator.” In the film, the Predator collects the skulls of the animals he has hunted. By the time he reached his

teenage years, Joshua, too, was a collector of the bleached out skeletal remains of animals long passed. Now 20 years into his career as an artist, Joshua is still combing through boneyards on ranches around Coleman to keep up his inventory for future assemblage art pieces. Sourcing bones with curvature is especially important to create torso-like

works that flow.

So, what is traditional about Joshua and Farrah’s found-object assemblage art pieces? “It’s archaic,” Joshua explains, “it’s in our blood; it’s in our muscle memory. This art form is actually so very old that a very ancient part of you would find it familiar.”

Pareidolia -- seeing patterns in random forms -- is what sets their work apart. Working in tandem, Joshua and Farrah envision new possibilities for their sun bleached boneyard finds. In this reimagining, a deer’s pelvis, turned about, may well be recast as the head on a fantastical bone sculpture with a name to suit -- Demetri! In the end, success translates to a finished piece that speaks to them. “We build them. They know what they want to look like when they’re done.” To Joshua’s way of thinking it’s almost a binary code: “Is this piece right, or is this piece wrong?”

Their love for connecting people to their art is a driving force for Joshua and Farrah. Yet, letting go of the work is often difficult without a closing reminder to the buyer: “There is only one of these in the world and it is yours!”

(Back to top)

Video by Zac Morgan and Texas Country Reporter

San Angelo | Tom Green County

Potter, Sculptor & Painter, Joe Morgan Ceramic Art

I think I love the process as much as I love the finished piece.

It’s not uncommon for Joe Morgan to wake up in the dead of night, struck with a creative idea. Captured with a quick note or scribble drawing, the concept may germinate for days, weeks, or even years before Joe acts on it, if at all. One concept for a beaded piece has been incubating in his sketch book for over 18 years.

Over time, Joe’s creative works have taken different turns. His hand-thrown  burnished horse hair pots are now one of his signature pieces. Joe learned the technique from potter/educator Randy Brodnax of Dallas over 20 years ago. As for his Whistlers clay sculptures series, they have been reimagined in different ways for over 17 years. The early learning process was taught to him by Jewel Gross Brenner.

burnished horse hair pots are now one of his signature pieces. Joe learned the technique from potter/educator Randy Brodnax of Dallas over 20 years ago. As for his Whistlers clay sculptures series, they have been reimagined in different ways for over 17 years. The early learning process was taught to him by Jewel Gross Brenner.

Joe’s first large-scale commissioned work, installed at San Angelo’s Shannon Oncology Center, Garden of Hope, is composed of 280 crosses welded together to form a 4’ x 6’ cross. “Painter,” another large-scale piece, is on display in Christoval, Texas. On a much smaller scale, Joe’s whimsical bottle cap snakes with their clay heads and tails -- a take-off on the colorful art snake he came upon in Santa Fe, New Mexico -- reflect his interest in works large and small.

With art projects always on his mind, Joe is acutely aware of what has made his envisioning possible. “That’s what your life is … one big everything that you do comes together sometime. That’s kinda what I do, now. I use the knowledge now that I gained a long time ago.”

(Back to top)

The Evolution of Clay with Joe Morgan

Santa Anna | Coleman County

Needlework & Weaving

I always have had a love of the needle. Anything that a needle is doing I’ve got to it give it a try.

Founded in 1885, Trickham is the oldest community in Coleman County, Texas. On Wednesdays a circle of hand quilters gather at the Trickham Community Center, just as many of their great-grandmothers did generations back. Linda Morris is always among them. “My thing is, I always have had a love of the needle. Anything that a needle is doing I’ve got to give it a try.”

An eager learner, under her mother’s watchful eye, by the time she was eight Linda was knitting and sewing, both by hand by hand and on a sewing machine. In seventh grade, as a 4-H Junior Leader, Linda stepped into the role of helping other students learn to sew.

Today, moving from knitting, crochet, and quilting, to spinning and loom weaving, Linda’s hands are always bus

y. When the word spread in Santa Anna about her sewing abilities the local visitors’ center came calling. Would she be interested in setting up a business at the center to make and sell her handmade wares? Up for the challenge, to draw visitors in, Linda hung one of her favorite crocheted tablecloths from the ceiling. Made up of intricate pineapple, wheat, and fishnet designs, the public response was staggering. “People were going crazy over it. What you can do with a crochet hook and a piece of string!”

Pursuing new learning opportunities keeps Linda’s brain active and alive. Passionate about her interests, she insists her “love of the needle” pursuits are not just hobbies, but a way of life that needs to be passed down.

(Back to top)

Coleman | Coleman County

Western Bootmaker, J.L. Palmer Boot Co.

If somebody’s not happy with them I’m gonna try to change them until they are.

Jamie Palmer grew up in a family that was all about horse training and cattle wrangling. And now, in true Texas form, custom bootmaking has become part of the mix.

Jamie’s first taste of bootmaking came by way of Guy Spikes at Brazos Boot Shop in Seymour, Texas. After buying a pair of custom boots from Guy, Jamie soon found herself hired on to stitch his boot tops. “It was tough at first … [you] put a pattern on and then you go one row at a time.” Impressed by her dedication and promise, Guy helped Jamie build a pair of boots so she could learn the process start to finish.

Though Jamie’s work would continue with Guy, in 2013 the Palmers moved to Coleman. Eager to expand her skill sets, in the fall of 2019, Jamie traveled to St. Jo for a two-week workshop with Carl Chapelle, the iconic Texas bootmaker. With seven other students, Jamie put in 12 hour days to learn Carl’s approach to his craft. “[His work] was like art work …[but] if I hadn’t had the base from Guy Spikes, I wouldn’t have learned as much.” Over time, after studying other bootmaker patterns, Carl assured the students they would start developing their own.

After Jamie’s return to Coleman, thanks to a major boost from Coleman’s economic development office, J. A. Palmer Boot Company opened its doors in a historic downtown storefront building. And now bolstered by a two-year waiting list, the future looks bright for one of Texas’ select female custom bootmakers.

(Back to top)

Norton | Runnels County

Stained Glass Artist

I didn’t know what was to become of [this], and I still don’t. You know, it’s just something I feel.

Fifteen years ago Lin Rostine and her husband, Bob, left the hectic city life behind. Norton, Texas, is now home with a population of 75, give or take. Surrounded by miles of unbroken farm and pastureland, Norton is a good place for contemplation. Lin admits, “Moving out here has just brought me down to a level I needed to be. It just made me learn more about myself and what I really believe in and what I really think.”

With pliers in hand, Lin breaks large shards of stained glass into smaller pieces, then carefully arranges them to create

the image she is envisioning. Her preference is to leave the glass rough-cut, and in some cases, to incorporate found objects into the piece. Lin’s work is a meeting place of sorts, where opposites attract: whim on the one hand, impassioned intent on the other. Now every stained glass piece she completes spurs her on to create another.

Retirement has given Lin time to pursue her own interests. Stained glass, in particular, was one medium that always interested her. In a small studio space built by her husband next to their home, Lin assembles her stained glass pieces from what comes to mind. “I didn’t know what was to become of [this] and I still don’t. You know, it’s just something I feel … I see something outside, or I see something in a magazine that catches my eye, and I want to build something pertaining to that. So that’s what I do.”

(Back to top)

Paint Rock | Concho County

Rug Weaver, Texas Handwoven Creations

It felt like it was coming full circle, a good next chapter. We don’t have a plan other than this is what we are doing for this season in our lives. Kind of holding the stewardship, I think of it, until the next owners come along. -Renee Farmer, Co-Owner, Texas Handwoven Creations

The looms are silent on the workroom floor as the team of six weavers at Texas Handwoven Creations take their morning break. “Ana’s loom,” affectionately termed, sits just inside the bank of windows at the front of the 100-year-old building. When the break is over the looms come to life once again. Soon the day’s production of new rugs begins to emerge in a play of horizontal patterns.

When Ana Ruiz hired on 15 years ago, after a month carding fleece, she began her training in the weaving room.

Born and raised in Zaragoza, Coahuila, Mexico, Ana came to the United States at the age of 16. Now married with four children, she has become the firm’s critical lead weaver, assigning jobs to her co-workers based on the order, size, and difficulty of the pattern. She is also responsible for training newly hired weavers. With Texas Handwoven Creations’ entire inventory of styles and sizes put to memory, Ana has now begun to design new creative rug patterns.

Renee and Tom Farmer purchased the business in 2017 from Reinhard Schoffthaler. Renee, fourth generation in the area, now lives with her husband on the land where her parents once raised sheep.

Today, Texas Handwoven Creations processes fleece from llama, alpaca, and buffalo. The fleece is shipped in from producers all over the nation; seconds and thirds, mostly, from the neck, underbelly, legs, and hind quarters. Once processed and woven into rugs, runners, or saddle blankets, the end products are sent back to the producers to be retailed.

(Back to top)

Eldorado | Schleicher County

Walking Sticks & Tomfoolery

You don’t stop laughing because you grow older; you grow older because you stop laughing.

With a crooked smile, Jim Runge shares the outlook that has made his days so bright: “Not one shred of evidence supports the notion that life should be taken seriously.” As a working man Jim spent most of his career in McKinney, the place where his impersonations at the monthly Lions Club meeting -- from Sam Houston to Elvis to Batman -- made him the talk of the town.

After some 30 years in McKinney, while transitioning back home to Eldorado, Jim caught the bug. It all began with his

determination to carve ten of his favorite impersonations on a walking stick. Three years in the making, today his “Totem Pole Personas” walking stick is Jim’s favorite among the 99 others he has crafted over the past 20 years. “Staff of Life” is Jim’s second favorite walking stick. Here, accumulated trinkets from his life pursuits are arranged in chronological order. “This is an ongoing project. Every half inch on this [60 inch] four-sided walking stick represents one year of my life; something I was doing at the time.” Jim’s walking sticks are created as pictograms to capture a wide range of life experiences and interests, from the conventional (Scouting) to the more idiosyncratic (mustaches). “It seems I create walking sticks for my different interests ... I have never sold one ... I seem to get attached to each one.”

Jim’s celebratory walking sticks are but a small sampling of his creations housed in an outbuilding at his ranch. Past the Rungini Medicine Show wagon, a t-shirt quilt hangs on the wall memorializing a few of the tomfoolery events Jim has staged through the years. Among them, the not to be forgotten ‘El Goatarod’ goat races around the Schleicher County Courthouse Square. And, oh yes, Jim’s ‘Running of the Bull’ competition with contestants vying to out-bull one another at the podium.

So what is Jim’s current fixation? Well, rock-by-rock, fine tuning the mega outline of the State of Texas he has created across 30 acres on his ranch!

(Back to top)

Eldorado | Schleicher County

Artist Blacksmith

Once people realize they can make things, it becomes a necessary part of their lives ... it opens up a part of the brain.

Early on, when Kevin Stanford signed up for a workshop at the Center for Metal Arts in New York with blacksmith Jake James, little did he realize how consequential the experience would be in helping him develop as an artist blacksmith. “Getting to know those folks I sort of stepped off into a really important artistic forging community. I am still friends with all of them.”

Kevin’s first blacksmith workshop was actually in Mississippi with Lyle Wynn. Penland  School of Craft summer workshops would follow in North Carolina with Dan Neville from the Center for Metal Arts (now located in Pennsylvania), James Viste from the College of Creative Studies in Michigan, and more recently, Claudio and Maximiliano Barrero based in Italy. “The iron studio at Penland,” Kevin notes, “is sort of the hot spot for people exploring new techniques.”

School of Craft summer workshops would follow in North Carolina with Dan Neville from the Center for Metal Arts (now located in Pennsylvania), James Viste from the College of Creative Studies in Michigan, and more recently, Claudio and Maximiliano Barrero based in Italy. “The iron studio at Penland,” Kevin notes, “is sort of the hot spot for people exploring new techniques.”

In Kevin’s view, once people realize they can make things it becomes a necessary part of their lives. “It opens up a part of the brain … everybody has got that … it just needs to be activated.” As for transitioning full-time to blacksmithing, “There came a time to work and do what [I] wanted to.” Once Kevin sorted out how to make ends meet for his family, he felt free to be more experimental, creating both utilitarian items and novel sculptural pieces.

San Angelo Art Club’s 2017 and 2019 “Artist of the Year,” Kevin’s work has been featured in both regional and national exhibitions, including two showings at the Center for Contemporary Arts in Abilene, Texas. New learning opportunities, as well as the ongoing inspiration and encouragement from his fellow blacksmiths, continue to move Kevin forward into new realms of possibility.

(Back to top)

Menard | Menard County

Traditional Leathercraft, Texas Heritage Woodworks

There are a lot of people that like the idea of going back to making things like they used to using traditional skills.

Jason Thigpen was raised in Bandera, Texas, where the local leathercraft, from bootmaking to saddle-making, remains a source of community pride. Although inclined early on to go the college route, Jason eventually found his way back to handwork, the place where he felt most at home.

Six years ago, frustrated at his inability to find a decent work apron, Jason set out to create his own, complete with  copper rivets. Once satisfied with the design, he posted a picture of the apron on his Instagram page to his 40 or so followers. In no time his first order came through. Once in hand, the buyer, ever delighted, posted a picture of his new apron on his Instagram page to his 1,200 followers. With that exposure, along with Jason’s move to develop more aprons with more options, demand for his one and only product offering just exploded. In short order Texas Heritage Woodworks was born.

copper rivets. Once satisfied with the design, he posted a picture of the apron on his Instagram page to his 40 or so followers. In no time his first order came through. Once in hand, the buyer, ever delighted, posted a picture of his new apron on his Instagram page to his 1,200 followers. With that exposure, along with Jason’s move to develop more aprons with more options, demand for his one and only product offering just exploded. In short order Texas Heritage Woodworks was born.

On the heels of the work apron came tool rolls, currently Jason’s biggest seller. The tool rolls are available in eight different styles including one configured to store auger bits. “I just try to find different things that people might find handy.” Next came saddle bags which sold out immediately.

Harkening back to his early years in Bandera, Jason has made it a point to integrate hand-stitched leather accessory items into his product line. A perfectionist, Jason’s standards are exacting. “Stitching is where I excel. Every stitch has to lay a certain way to look just right.”

(Back to top)

Live Oak | Concho County

Western Gearmaker

I was ten years old when I went to work at the ranch ... as I got older I would take a saddle apart and redo it myself.

Eager to follow in his father’s footsteps as a working cowboy, Victor Torres dropped out of school at an early age. “I was ten years old when I went to work at the ranch … from then on until I was 21. The school that I learned working with [my father] was being responsible, respectful of everybody and their property, and loving the life out in the country.”

With a growing interest in bootmaking, Victor hired on at M. L. Leddy’s, the iconic bootmaker in San Angelo, Texas.

At Leddy’s he was schooled in the many tasks that go into building a boot. Later Victor signed on with J. L. Mercer, another well known bootmaker in San Angelo. Ramiro, the shop foreman at the time, brought Victor’s bootmaking skills up to another level. “I appreciated that because he taught me to do something I loved, relaxing to your mind, to your heart, with no time to think who is doing what anywhere.” Working out of his own shop, Victor later switched gears to begin stitching boot tops for Robert Brest, yet another celebrated San Angelo bootmaker.

At Leddy’s he was schooled in the many tasks that go into building a boot. Later Victor signed on with J. L. Mercer, another well known bootmaker in San Angelo. Ramiro, the shop foreman at the time, brought Victor’s bootmaking skills up to another level. “I appreciated that because he taught me to do something I loved, relaxing to your mind, to your heart, with no time to think who is doing what anywhere.” Working out of his own shop, Victor later switched gears to begin stitching boot tops for Robert Brest, yet another celebrated San Angelo bootmaker.

With his years of experience as a working cowboy, along with a head full of knowledge on the ins and outs of leather crafting, Victor’s cowboy gear offerings now range beyond his own handcrafted custom boots to include chaps, chinks, tapaderos and rope bags.

Tending to his horses and cattle, a chuck wagon set for the next cook-off, and a fully equipped workshop for gearmaking, Victor is keeping the region’s working cowboy traditions alive and well for future generations.

(Back to top)

Toddler Tours with Lucille and Bekah

Zane Blackwell

Zane Blackwell  Lee Bloodworth

Lee Bloodworth

Wilson Capron

Wilson Capron

udrey Legatowicz

udrey Legatowicz alorie Lewis

alorie Lewis

inda Morris

inda Morris

in Rostine

in Rostine

im Runge

im Runge

ictor Torres

ictor Torres